The Story of the Presbyterians in Ulster

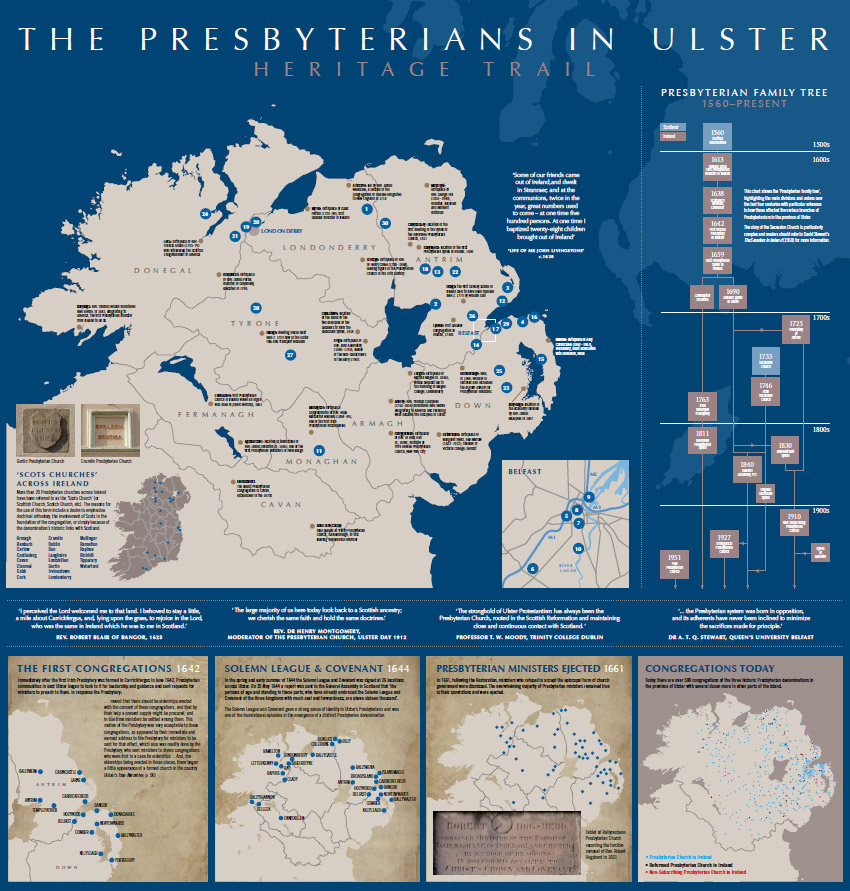

For four centuries Presbyterians have represented one of the most important elements in the population of Ireland. Their influence has been strongest in the history of the northern province of Ulster where for over 300 years they have constituted a majority of the Protestant population. The origins of the Presbyterian churches in Ireland can be traced to Scotland and to the successive waves of immigration of Scottish families to this island in the 1600s.

This publication looks at the story of Ulster’s Presbyterians, highlighting the emergence of the historic Presbyterian denominations, the role of Presbyterians in the 1798 Rebellion and the formation of Northern Ireland, and the contribution of Presbyterians to education and the mission field. It also includes information on 30 sites where you can discover at first hand the richly textured history of Presbyterianism in Ulster.

Presbyterian Historical Society of Ireland

The Presbyterian Historical Society of Ireland was founded in 1907. The Society’s aims are to preserve and promote the history of the churches of the Presbyterian order in Ireland – the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, the Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church of Ireland and the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Ireland. The Society maintains a library and archive at 26 College Green, Belfast, and welcomes members and visitors to consult its resources. It also organises an annual lecture programme and a summer outing, and publishes materials relating to the history of Irish Presbyterianism in print and online.

www.presbyterianhistoryireland.com

Ulster Historical Foundation

Established in 1956, the Ulster Historical Foundation’s mission is to tell the story of the people of the nine counties of the historic province of Ulster. It achieves this through a comprehensive range of professional research, publishing and heritage services. The Foundation maintains a library of genealogical and historical materials. Each year the Foundation conducts an annual lecture tour in North America and organises family history conferences in Ireland, combining opportunities for research in the archives with visits to places of historic interest.

1. The First Ministers

Early 17th-century Ireland was in a state of transition and in no part of the island was this more apparent than in Ulster. As a result of official and unofficial plantations there was an influx of settlers from England and, in particular, Scotland which transformed the character of much of the province.

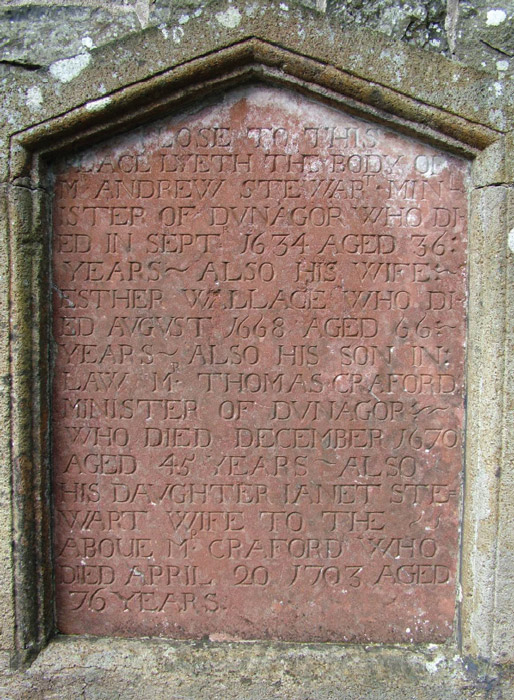

Accompanying these settlements was the introduction of Protestantism. The Church of Ireland was the established or state church and was organised along episcopalian lines. However, a number of ministers came to Ulster in this period who dissented from this view of church government, preferring the presbyterian system. In part, their move to Ulster was due to the increasing hostility of the authorities in Scotland to presbyterianism. The first of these men was Rev. Edward Brice who moved from Drymen in Stirlingshire to Ballycarry in County Antrim in 1613. He was followed by, among others, Rev. Robert Blair in Bangor, and Rev. John Livingstone in Killinchy, both County Down, Rev. Andrew Stewart in Donegore, and Rev. Josias Welsh in Templepatrick, both County Antrim. To begin with such men were tolerated within the Church of Ireland and there was no separate presbyterian denomination at this time.

One of the most significant episodes in the development of early presbyterianism in Ulster was the Six Mile Water Revival which left a deep impression on the Scottish communities of Antrim and Down in the late 1620s and early 1630s.

In the 1630s the government took steps to bring the Church of Ireland into closer conformity with the Church of England. As a result of these measures, those ministers who were not prepared to renounce their presbyterianism were excommunicated. In 1636 four ministers (Blair, Livingstone, James Hamilton and John McLellan), with about 140 followers, set sail in the Eagle Wing for America with the intention of establishing a Presbyterian colony in New England; they never reached their destination as storms drove the ship back.

2. The First Presbytery

In Scotland attempts by Charles I to impose his authority upon the Church provoked a hostile response which eventually led to the National Covenant of 1638. This Covenant declared presbyterianism the only true form of church government and bound the nation to the principles of the Reformation.

Many people in the north of Ireland also signed this Covenant. In response, the government insisted that all Scots in Ulster over the age of sixteen take an oath – the ‘Black Oath’ as it became known – abjuring the Covenant. This had a deeply destabilising effect on the province with many settlers withdrawing to Scotland to avoid taking the oath.

In October 1641 an uprising began in Ulster which was organised by the leading figures in the Gaelic Irish community. This insurrection quickly escalated and resulted in significant loss of life and destruction of property. Many of the Scottish settlers fled for safety to their homeland, while in 1642 an army under the command of Major General Robert Munro was sent to Ireland to protect those who remained.

The regiments in this army were accompanied by ministers who acted as chaplains. They included:

- Rev. Hugh Cunningham

- Rev. John Baird

- Rev. Thomas Peebles

- Rev. James Simpson

- Rev. John Scott

- Rev. John Aird

On 10 June 1642, in Carrickfergus, County Antrim, five of these ministers and four ruling elders, chosen from the four regiments that had formed kirk sessions, came together in what is regarded as the inaugural Irish Presbytery meeting, from which, in a formal sense, today’s Presbyterian Church in Ireland descends. This event is commemorated by a sculpture positioned beside Joymount Presbyterian Church, Carrickfergus, and by the ‘Carrickfergus Window’ in Assembly Buildings, Belfast.

3. The Covenant and Ulster

Presbyterians across Ulster looked to the new Presbytery for leadership and spiritual guidance. As kirk sessions were formed and as ministers were appointed to preach in various districts, the Presbyterian Church began to put down deep roots in Ulster.

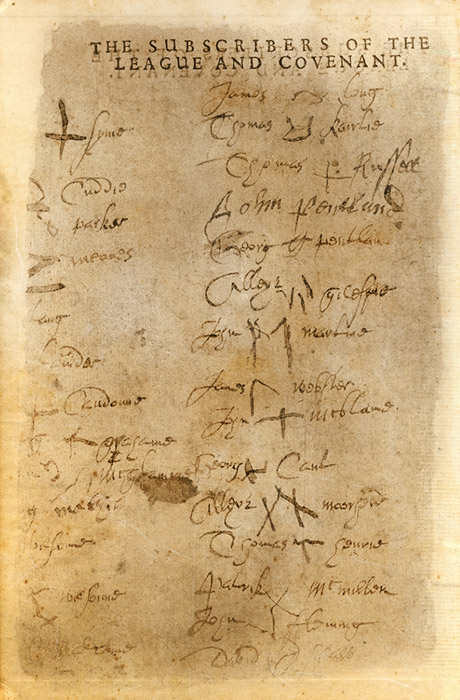

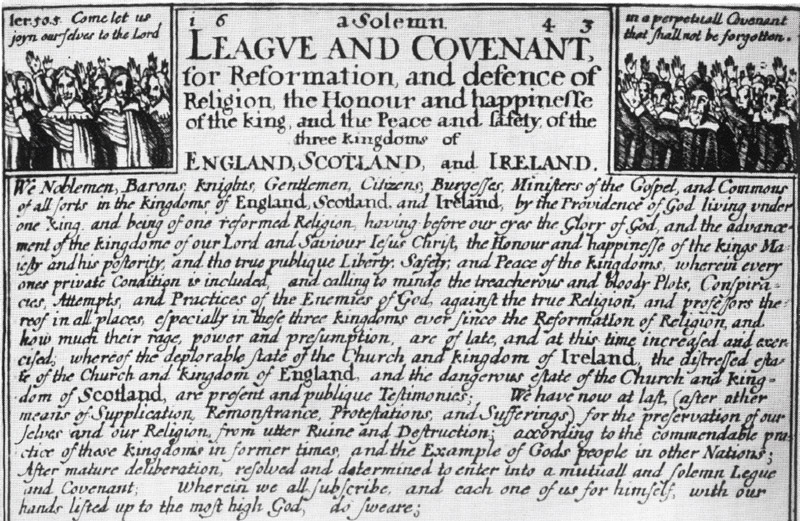

In response to wider political developments across the three kingdoms, the Solemn League and Covenant was prepared in 1643 by Scottish Covenanters and English Parliamentarians. In return for a promise to reform the Church in England and Ireland along presbyterian lines the Scots agreed to provide military support to the Parliamentarians in their conflict with Charles I.

In April 1644 orders were issued from Scotland that the Solemn League and Covenant should be administered to the Scottish army where it was garrisoned throughout Ulster and to anyone else who wished to subscribe to it. Over the next three months, the Covenant was administered to thousands of people at 26 locations across the province, from Ballywalter in County Down to Ballyshannon in County Donegal. The copy of the Covenant signed at Holywood is in the collection of the Ulster Museum in Belfast.

The Parliamentarians, now led by Oliver Cromwell, failed to deliver on their promise to reform the Church of England as a Presbyterian denomination and when they executed the king in 1649 they were roundly condemned by Ulster’s Presbyterians. Despite its uneasy and at times fractious relationship with the Cromwellians, the Presbyterian Church continued to grow during the 1650s and many more ministers from Scotland moved to the north of Ireland.

During this decade the structures of the Presbyterian Church developed further with the creation of a number of regional ‘meetings’, such as the Route in north Antrim and the Laggan in the Foyle Valley. In 1659, at Ballymena, County Antrim, Presbyterians gathered for what has been described as the first synod in Ireland.

4. The Late 17th Century

Following the Restoration of 1660, ministers who refused to conform to the teachings and episcopal authority of the newly reinstated Church of Ireland were dismissed. One virulent opponent of the Presbyterian ministers was Bishop Jeremy Taylor of Down and Connor who in one day declared vacant 36 parishes in counties Antrim and Down.

In the years that followed there was considerable state hostility towards Presbyterians and at different times ministers were arrested and imprisoned. One particularly notorious incident followed the discovery in 1663 of a conspiracy by Captain Thomas Blood to seize Dublin Castle. Around 20 Presbyterian ministers were arrested on suspicion of complicity in this plot, but all were eventually released with the exception of Blood’s brother-in-law, Rev. William Lecky, who was executed.

In 1684, during another difficult period for Presbyterians, some ministers in County Donegal considered emigrating to America to escape persecution, but in the end did not go ahead with this. Despite these difficulties, Presbyterians continued to form congregations and, having been excluded from parish churches, began to build their own meeting houses.

Many Ulster Presbyterians fought for the Williamite cause at Derry, the Boyne and elsewhere. On 19 June 1690, King William III, while at Hillsborough, restored and increased the regium donum, a bounty that had first been paid to Presbyterian ministers by the government in 1672. A few months later synodical meetings resumed with the formation of the General Synod of Ulster.

The aftermath of the Williamite war saw a new influx of thousands of Scots into the north of Ireland, encouraged by harvest crises in their native land and the prospect of new opportunities in Ulster. Around 1700 William King, the bishop of Derry, observed that due to a fresh wave of migration from Scotland, ‘the dissenters measure mightily in the north’. By this time Presbyterians comprised a majority of Protestants in Ulster.

5. The 18th Century

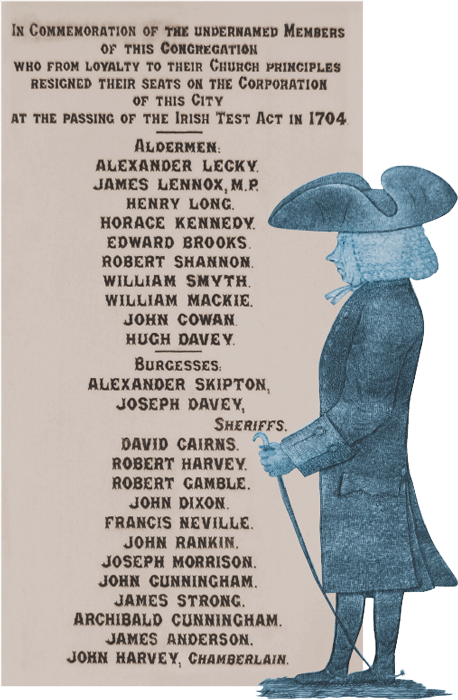

In 1704 the Test Act was introduced in Ireland which required those holding public office to produce a certificate stating that they had received communion in an Anglican church. This effectively disbarred Presbyterians from participation in local government. In 1719, with the passing of the Toleration Act, Presbyterians were granted official recognition. Nonetheless, with the levers of power still firmly in the hands of an Anglican elite, and with other restrictions still in force, they continued to feel estranged from the state.

The relationship with the state was only one of the issues confronting the Presbyterian Church in this period. For the first time a serious internal dispute threatened the unity of the Church.

The Church also faced the challenge of two alternative versions of Presbyterianism in the form of the Covenanters and the Seceders. Nonetheless, the Church maintained its position as the dominant Presbyterian denomination on this island.

In 1704 the Test Act was introduced in Ireland which required those holding public office to produce a certificate stating that they had received communion in an Anglican church. This effectively disbarred Presbyterians from participation in local government. In 1719, with the passing of the Toleration Act, Presbyterians were granted official recognition. Nonetheless, with the levers of power still firmly in the hands of an Anglican elite, and with other restrictions still in force, they continued to feel estranged from the state.

The relationship with the state was only one of the issues confronting the Presbyterian Church in this period. For the first time a serious internal dispute threatened the unity of the Church.

The Church also faced the challenge of two alternative versions of Presbyterianism in the form of the Covenanters and the Seceders. Nonetheless, the Church maintained its position as the dominant Presbyterian denomination on this island.

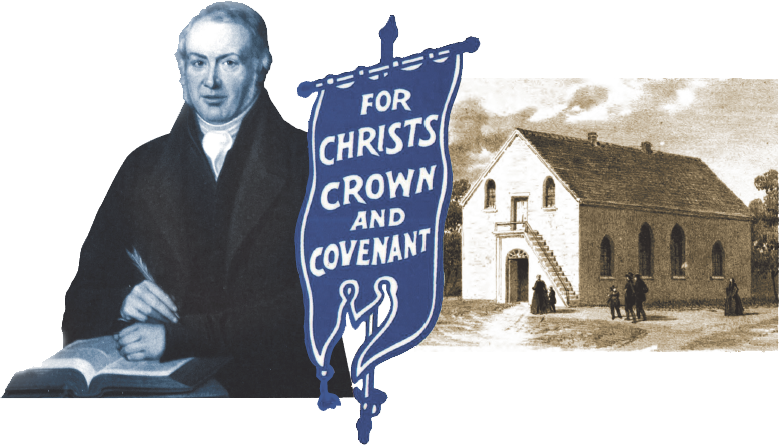

6. The Covenanters

By the 1680s a majority of Presbyterians had come to a position on the Covenants of 1638 and 1643 which could be described as ‘respectful remembrance’. That is, they believed that the Covenants had been important documents, but were no longer perpetually binding on them and their descendants.

On the other hand, a minority of Presbyterians continued to believe in the continuing obligation of the Covenants and from them today’s Covenanters or Reformed Presbyterians descend.

Of the early history of the Covenanters in Ireland very little is known, save that their numbers were small and that they were widely scattered. They maintained close links with fellow Covenanters in Scotland where a Reformed Presbytery was formed in 1743. The first Reformed Presbyterian minister, Rev. William Martin, was ordained at The Vow on the River Bann, near Ballymoney, in 1757. Six years later an Irish Reformed Presbytery was established. Due to a depleted ministry this was dissolved in 1779 but was re-established in 1792. In 1811, at Cullybackey, County Antrim, a Synod of the Reformed Presbyterian Church met for the first time.

The 1830s was a decade of dissension within the Reformed Presbyterian Church over issues relating to the denomination’s historic position on political dissent and in particular on the powers of the civil magistrate. Eventually, led by Rev. John Paul of Loughmourne, County Antrim, those who challenged the accepted view withdrew from the main body of the Church in 1840 and formed the Eastern Reformed Presbyterian Church. This denomination folded in the early 20th century with most congregations either joining the Presbyterian Church or returning to the Reformed Presbyterian Church.

Today there are some 40 congregations, societies and fellowships in the Reformed Presbyterian Church in Ireland with several new causes established in recent years.

7. The Non-Subscribers

In the early 18th century, there occurred the first major dispute within Irish Presbyterianism. This was over the issue of subscription to the Westminster Confession of Faith which had been made compulsory on all ministers by the Synod of Ulster. Led by Rev. John Abernethy of Antrim, those who denied the necessity of subscribing to this work were known as ‘New Lights’ or ‘Non-Subscribers’.

Failing to reach a consensus on the issue, in 1725 the Synod of Ulster placed those who took this stance in the Presbytery of Antrim (this did not mean that all of the congregations were in County Antrim). In the following year the Synod voted to exclude the Presbytery of Antrim from the courts of the church.

A century later the issue of subscription again arose and was exacerbated by the division on the issue by conservative and liberal elements within the Synod, the former favouring compulsory subscription. Eventually this led to the withdrawal from the Synod of Ulster of seventeen ministers, led by Rev. Henry Montgomery of Dunmurry, and the formation of the Remonstrant Synod of Ulster in 1830, which held its first annual meeting in Belfast in May of that year. In 1835 the Remonstrant Synod, the Presbytery of Antrim and the Synod of Munster came together to form the Association of Irish Non-Subscribing Presbyterians.

In 1910 the General Synod of the Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church was formed by the Presbytery of Antrim and Remonstrant Synod. In the 1930s the Synod of Munster also joined this body. Today the 34 congregations of the Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church are found exclusively in counties Antrim and Down, with the exception of the congregations in Cork and Dublin. The denomination has as its motto, ‘Faith guided by reason and conscience’.

8. The Seceders

Following a dispute in the Church of Scotland over the issue of patronage and concerns about doctrinal laxity, a number of ministers seceded (hence their appellation Seceders) in 1733 and formed the Associate Presbytery. The conservative evangelicalism of the Seceders appealed to many Presbyterians in Ulster and from the 1740s onwards Seceder congregations were established here.

As a general rule, it would appear that it was in those areas most strongly affected by the influx of families from Scotland in the years either side of 1700 that the Seceders made the greatest impact. The first Seceder congregation in Ireland was at Lylehill, County Antrim. In 1741 Presbyterians in this district appealed to the Associate Presbytery in Scotland to send them preachers. Occasional preaching supplies were provided for several years before Isaac Patton, a native of Myroe, near Limavady, County Londonderry, was ordained their minister in 1746.

The Seceders in Scotland divided over the issue of the Burgess Oath, giving rise to the Burghers and Antiburghers. Though this division had little relevance to Ireland, nonetheless, the Seceders here separated into the two camps. The Burghers established a Synod in 1779 in Monaghan and the Antiburghers did so in 1788 in Belfast.

A growing realisation that what they held in common was far greater than what divided them led to the Burghers and Antiburghers coming together to form the Secession Synod at Cookstown in 1818. In 1840 the great majority of Seceder congregations joined with the Synod of Ulster in forming the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church. A few Seceder congregations remained outside of this body, but in time most joined the General Assembly, though a few joined the Reformed Presbyterian Church.

9. Presbyterians and The 1798 Rebellion

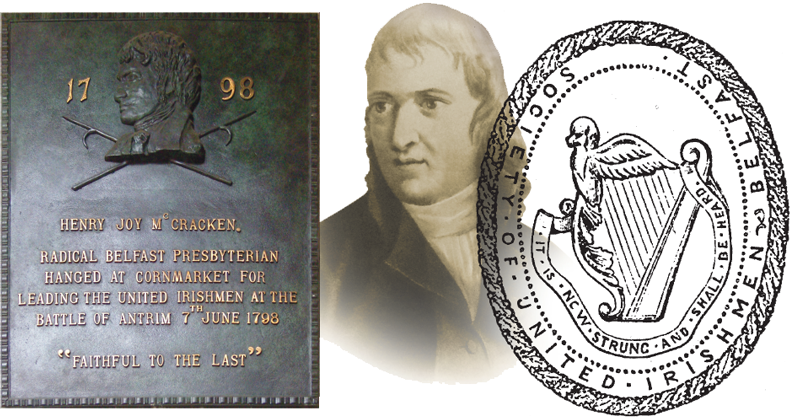

The distinguished historian A.T.Q. Stewart famously observed, ‘The Presbyterian is happiest when he is being a radical.’ Political radicalism was never more obvious than in the 1790s when Presbyterians were instrumental in the creation of the United Irishmen and were heavily involved in the revolutionary activities that led to the 1798 Rebellion.

Influenced by the American and French Revolutions the Society of United Irishmen was founded in Belfast in 1791 by a group of Presbyterians led by Dr William Drennan, son of a former minister of the First Presbyterian Congregation in the town. Soon afterwards clubs were founded in Dublin and a number of other places. The aims of the Society were parliamentary reform and the elimination of English interference in Irish matters. After efforts to suppress it, the Society reorganised itself as a secret organisation and began to prepare for rebellion.

Following a failed French expedition in December 1796, the repressive measures taken by the government in 1797 severely weakened the United Irishmen in Ulster. Rebellion began in Leinster in late May 1798. On the night of 6–7 June it spread to Ulster when a party of United Irishmen advanced into Larne and forced a contingent of government troops back to their barracks. Soon afterwards Ballymena and Randalstown were taken, but at Antrim Town the rebels were defeated.

In County Down following an initial victory at Saintfield, the rebels were roundly defeated at nearby Ballynahinch on 11 June and the rebellion in Ulster was all but finished. There followed a series of executions including that of Rev. James Porter of Greyabbey, the only ordained minister of the Presbyterian Church to be put to death in what was widely regarded as a miscarriage of justice. One of the last to be hanged was the most famous Ulster rebel of them all, Henry Joy McCracken, a member of the Third Presbyterian Congregation, Belfast.

10. Presbyterianism in the 1800s

The 19th century was a period of expansion for the Presbyterianism in Ireland with hundreds of new congregations formed, partly in response to the rise in the population in the early 1800s, and also to the expansion of urban centres. This can be seen clearly in the rapidly expanding industrial city of Belfast where between 1850 and 1900 the Presbyterian population quadrupled, while the number of congregations rose from 15 to 47.

The withdrawal of the liberals in the late 1820s helped to clear the way for the union of the Synod of Ulster and the Secession Synod. In 1840 the ruling bodies of these two denominations came together to form the General Assembly that comprised nearly 450 congregations and some 650,000 members.

The 19th century saw the Presbyterian Church in Ireland establish overseas missions. In 1840 the General Assembly commissioned Rev. James Glasgow and Rev. Alexander Kerr to go as missionaries to India. Many others would follow as other missions were established in China as well as missions to the Jews and Colonial and Commonwealth missions.

One of the most dramatic events in Irish religious history was the 1859 Revival. A spiritual awakening, of a depth and power that had never been experienced before, spread through Ulster at a remarkable pace. While the Revival affected Protestants from all denominations, it was particularly associated with the Presbyterian Church.

The position of Presbyterians within wider society was also improving. Most Presbyterians became reconciled to the reality of the union with Britain and were liberal in their political outlook. They welcomed the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland (which also saw the ending of the regium donum) and the land reforms that benefited farmers introduced by the Liberal government at Westminster led by W. E. Gladstone. However, from 1886 onwards, Presbyterians overwhelmingly rejected Gladstone’s proposals for Home Rule which proposed a devolved parliament in Dublin.

11. Presbyterianism Since 1900

Presbyterians entered the twentieth century with confidence, a clear sense of purpose, and with a pride in their contribution to the modernising of Ulster as well as a strong awareness of their Scottish roots. This was symbolised in the opening of a new headquarters for the Presbyterian Church – the magnificent Assembly Buildings – in Belfast in 1905.

During the third Home Rule crisis of 1910–14, unionists drew on the 17th-century Scottish covenants in formulating a document – the Ulster Covenant – that would express their deep opposition to proposed changes to their position within the United Kingdom.

The partition of Ireland in 1921 was viewed by Presbyterians as a ‘regrettable necessity’. While most Presbyterians now found themselves within the new state of Northern Ireland, a significant minority in the border counties of Ulster and in other parts of the island – some 50,000 – were in the Irish Free State, the forerunner of the Republic of Ireland.

The recent ‘Troubles’ was a period of intense trial for many Presbyterians. Many Presbyterians died as a result of terrorist atrocities during the conflict and many more were injured.

In the 21st century the Presbyterian Church faces the major challenge of secularism and the increasing disinterest in matters of religion. A number of congregations, especially in inner city Belfast and on the west bank of the River Foyle in Londonderry, have folded, while others are at risk of closure. Nonetheless, in other areas new congregations have been established and existing causes revitalised.

Today the Presbyterian Church continues to maintain a witness and carry on a tradition that began in Ireland four centuries ago. At present there are some 560 congregations and around 230,000 members of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland. While its presence is mainly to be found in Northern Ireland, there are significant numbers of congregations in other parts of the island, especially counties Donegal and Monaghan as well as the city of Dublin.

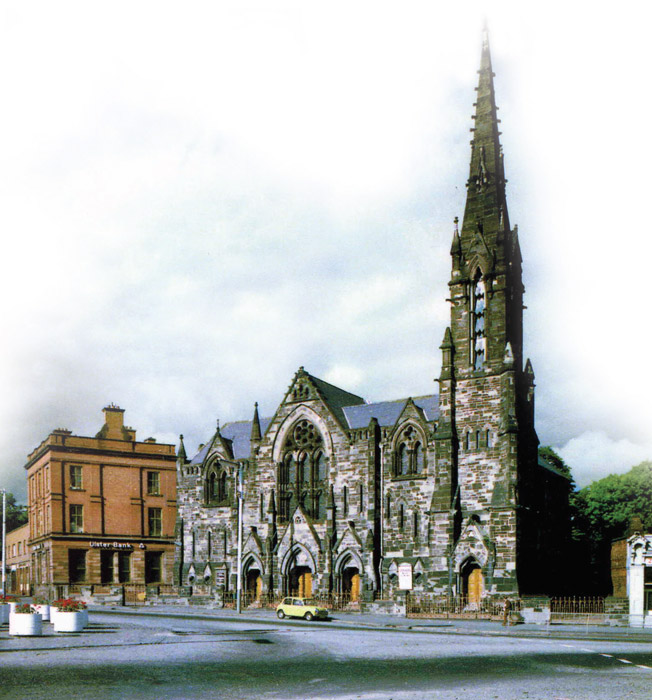

12. Presbyterian Places of Worship

It was not until the second half of the 17th century that Presbyterians in Ireland began to build their own places of worship. (Prior to this they met in the parish churches of the Established Church.) To begin with Presbyterian meeting houses were built in less conspicuous rural areas or on the edge of towns.

Lacking wealthy patrons, most Presbyterian congregations did not build architecturally distinguished meeting houses. Rather in their design and configuration these places of worship reflected the Presbyterian emphasis on preaching and the need for everyone to hear the message.

The typical 18th-century Presbyterian meeting house was built on the T-plan with the pulpit in the centre of the long wall. If extra room was needed galleries would be added with access to them usually via external staircases. More innovative designs can be seen in the First Presbyterian Church, Belfast, and the Old Congregation, Randalstown, County Antrim, which are elliptical in plan.

In the 18th and early 19th century the preference for Classicism was a reflection of stylistic influences from Scotland and the rejection of the Gothic of both the Roman Catholic Church and Church of Ireland. Good examples of Classical churches include May Street, Belfast, constructed for Rev. Dr Henry Cooke; Castlereagh, the first Presbyterian church to be built with a belfry; and Portaferry, regarded as one of the finest Neoclassical buildings in Ireland.

Gothic architecture, for long eschewed by Presbyterians, became increasingly popular during the Victorian period and was the preferred style for many new churches built in the second half of the 1800s, e.g. Fitzroy and Fortwilliam in Belfast. In recent decades a variety of modern styles have been employed on new church buildings, many of which were built in response to new works starting in post-war housing developments.

13. Education and Social Concerns

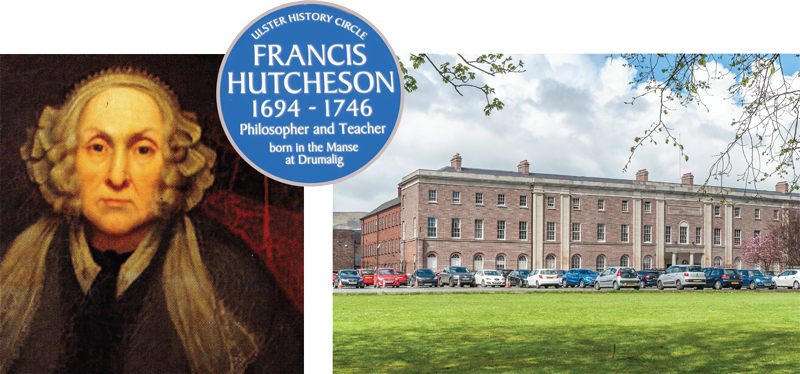

The Presbyterian Churches have always placed a high premium on education, not only in terms of an educated ministry, but also in having a literate membership. Many Presbyterian ministers organised their own schools. One of the earliest of these was the school established by Rev. James McAlpine at Killyleagh, County Down, in 1697 where Rev. Francis Hutcheson, later Professor of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University, received some of his early education.

In the second half of the 18th century notable academies were found at Rademon, County Down, by Rev. Moses Neilson and at Strabane, County Tyrone, by Rev. William Crawford. The driving force behind the opening of Belfast Academy in 1786 was a Scotsman, Rev. Dr James Crombie, minister of the First Presbyterian Congregation, who wanted to establish a school along the lines of a Scottish collegiate institution.

Prior to the 19th century the overwhelming majority of Presbyterian ministers received their university education in Scotland, for the most part in Glasgow. However, the opening in 1815 of Belfast Academical Institution with its collegiate department meant that it was now possible for Presbyterians to receive a higher education without having to travel to Scotland. Later in the 19th century Assembly’s College was founded to train ministers for the Presbyterian Church, while Magee College in Londonderry, founded through the generous bequest of the widow of a Presbyterian minister, offered courses in arts and divinity.

In the 19th century many Presbyterians became actively involved in ventures designed to promote moral improvements in society and reach out to the unchurched. These included the Temperance movement, championed by such figures as Rev. Dr John Edgar in Belfast and Anne Jane Carlile, the subject of a blue plaque at Trinity Presbyterian Church, Bailieborough, County Cavan. Organisations founded by Presbyterians, or with which they became actively involved, included the Presbyterian Orphan Society (now the Children’s Society) and the Belfast Town (later City) Mission.

14. Ulster Presbyterians Worldwide

For more than three centuries Presbyterians from Ulster have been carrying their faith across the globe – to North America, Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere –and have founded many congregations and built numerous places of worship.

Emigration to North America by Ulster Presbyterians began in the late 17th century. Immigrants from Ulster made a huge contribution towards the development of Presbyterianism in America, none more so than the Donegal-born Rev. Francis Makemie who sailed across the Atlantic in 1683. His pioneering ministry earned him the title, ‘Father of American Presbyterianism’.

Presbyterian ministers have been key drivers of emigration from Ulster. In 1718 Rev. James McGregor of Aghadowey in the Bann Valley led part of his congregation to New England, as did Rev. James Woodside of Dunboe. In 1764 Rev. Thomas Clark of Cahans, County Monaghan, led 300 Presbyterians to America, while in 1772 Rev. William Martin led a major exodus of Covenanter families, mainly from County Antrim, to South Carolina.

Regarded as the man who introduced the Scottish Enlightenment to America, Rev. Francis Alison was born into a family of relatively modest means at Leck, County Donegal, in 1705. Several of his students would go on to sign the Declaration of Independence. Around the time of the 1798 Rebellion a number of Presbyterian ministers and probationers withdrew to America on account of their support for the United Irishmen. They included David Bailie Warden from Bangor who went on to serve as US Consul at Paris.

More than a dozen of the descendants of Ulster Presbyterian migrants succeeded to the presidency of the United States, among them Andrew Jackson, James Buchanan and Woodrow Wilson. One of the most highly regarded presidents, Wilson was born in the Presbyterian manse in Staunton, Virginia, and grew up very conscious of his heritage. He once said, ‘The stern Covenanter tradition that is behind me sends many an echo down the years.’

15. Tracing Presbyterian Ancestors

Today an ever-increasing number of people from around the world are interested in finding out more about their Ulster Presbyterian ancestors. The same challenges that face those researching Irish ancestors in general also apply to those looking specifically for Presbyterian forebears.

Though there are some registers of baptisms and marriages (Presbyterian congregations generally did not keep registers of burials/deaths prior to the 20th century) dating from as far back as the late 17th century, most Presbyterian registers survive from the 19th century.

The various levels of church government within the Presbyterian denominations have also created records of use to genealogists. At congregational level the records include session books which cover a range of matters, many of which relate to the internal discipline of members. They can also refer to the issuing of transfer certificates to members leaving a congregation, often because they were emigrating overseas.

The financial records of a congregation range from stipend lists (the stipend being the minister’s salary) to pew rent books and account books. Communicants’ lists were also kept, and these can be annotated with additional information, such as when a communicant married, emigrated or died. Occasionally there may be a congregational census.

The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (www.nidirect.gov.uk/proni) has registers of baptisms and marriages for the great majority of congregations of the different Presbyterian denominations in the province of Ulster. Usually, these records are available on microfilm, though there are some originals.

The Presbyterian Historical Society (www.presbyterianhistoryireland.com) also has microfilm copies of registers as well as some congregational records that are not available elsewhere. In addition, it holds many administrative records and publications relating to Irish Presbyterianism. The records of a few congregations are still held locally. Thanks to the internet an increasing number of Presbyterian records can now be accessed online.